From Barefoot Classrooms to Battlefields: How Decades of Neglect Turned Almajiri Children into Nigeria’s Insecurity Time Bomb

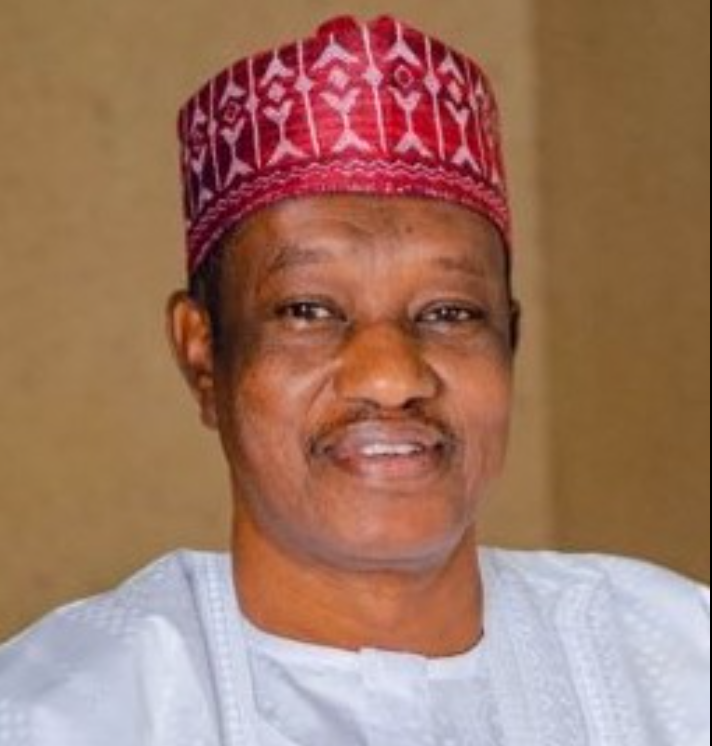

Nigeria’s worsening insecurity did not begin with the crack of gunfire in forests or the daring raids on highways; it began decades ago in silence, neglect and missed responsibility. That was the sobering message delivered by former Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Samuel Olajide Afolyan (retd.), who traced today’s banditry and violent criminality to leadership failures dating as far back as the 1980s. Speaking at the OSI Day 2025 event, Afolyan said many of the Almajiri children roaming the streets during his years of active service have now grown into the armed bandits terrorising communities across the country.

His remarks struck a painful chord at a time when Nigeria is grappling with persistent kidnappings, rural banditry, insurgency and widespread insecurity that has claimed thousands of lives and displaced entire communities. According to Afolyan, the crisis is not merely a security failure but the harvest of decades of neglect in education, social welfare and moral development. What Nigeria is experiencing today, he argued, is the predictable outcome of abandoning millions of vulnerable children to fend for themselves without structure, protection or opportunity.

The Almajiri system, which traditionally involved young boys studying Islamic teachings under clerics, gradually collapsed under the weight of poverty, population growth and lack of regulation. Instead of receiving balanced education and care, many children were pushed onto the streets to beg for survival. Afolyan recalled encountering these children during the 1980s, barefoot, malnourished and largely ignored by the state. At the time, he said, the warning signs were visible, but successive governments failed to act decisively.

Decades later, those same children are now adults in a society that never invested in them. Without formal education, vocational skills or social support, many found identity, survival and power in criminal networks. Forests became their refuge, weapons their tools and violence their language. Afolyan’s assertion challenges the popular narrative that treats insecurity solely as a military problem, instead framing it as a social consequence rooted in years of policy neglect.

At OSI Day 2025, the retired naval chief did not mince words as he called on Nigerian politicians to engage in deep self-reflection. He urged leaders to reassess their contributions to society, particularly towards those most at risk. According to him, governance should not be measured only by infrastructure projects or political victories, but by how a nation protects its children, cares for its elderly and uplifts its poorest citizens.

“I’ll encourage our politicians to go to the drawing board again and look at what contribution are we making to make life easy for our elders, the old women, our children,” Afolyan said, stressing that leadership carries moral responsibility beyond office tenure. His message resonated strongly in a country where political debates often overshadow long-term human development planning.

Security analysts have increasingly echoed similar views, noting that military operations alone cannot end banditry or insurgency. While security forces may neutralise immediate threats, the underlying pipeline that feeds criminal groups remains active as long as poverty, illiteracy and social exclusion persist. Nigeria’s large youth population, when left without education or economic prospects, becomes a fertile recruitment ground for violent actors.

Afolyan’s remarks also highlight a generational failure that transcends political parties and regions. The neglect of Almajiri children was not the decision of one administration but a collective oversight spanning decades. Policies were either poorly implemented or abandoned entirely, while social welfare systems remained weak. Attempts to reform the Almajiri system through modern schools and integration programmes were sporadic and underfunded, leaving millions unreached.

Today, the cost of that neglect is staggering. Farmers abandon their lands due to fear of attacks, food prices soar, and rural economies collapse under insecurity. Children now grow up in communities traumatised by violence, risking the creation of yet another generation shaped by fear and survival instincts rather than education and hope. Afolyan warned that without urgent corrective action, the cycle will continue.

His intervention comes amid renewed calls for holistic solutions that combine security enforcement with education reform, social investment and community rehabilitation. Experts argue that addressing insecurity requires rebuilding trust between the state and citizens, ensuring access to quality education, and creating economic pathways for young people who might otherwise drift into crime.

The former naval chief’s words also serve as a moral indictment of leadership culture in Nigeria, where short-term political gains often take precedence over long-term national stability. By ignoring vulnerable populations, leaders inadvertently sow the seeds of future crises. Afolyan’s reflection from the 1980s to today offers a rare long-view perspective, reminding Nigerians that today’s emergencies are often yesterday’s neglected responsibilities.

As Nigeria debates solutions to its security challenges, Afolyan’s message adds a human dimension to the conversation. Behind every armed bandit, he suggests, is a story that began with abandonment. While this does not excuse criminality, it demands a more honest assessment of national failures and a commitment to preventing similar outcomes in the future.

The question now is whether Nigeria’s leaders will heed this warning or allow history to repeat itself. With millions of children still vulnerable across the country, the choices made today will determine whether the nation finally breaks the cycle of neglect or continues to pay the price in blood and instability. For Afolyan, the lesson is clear: when a society fails its children, those children eventually return as its greatest challenge.