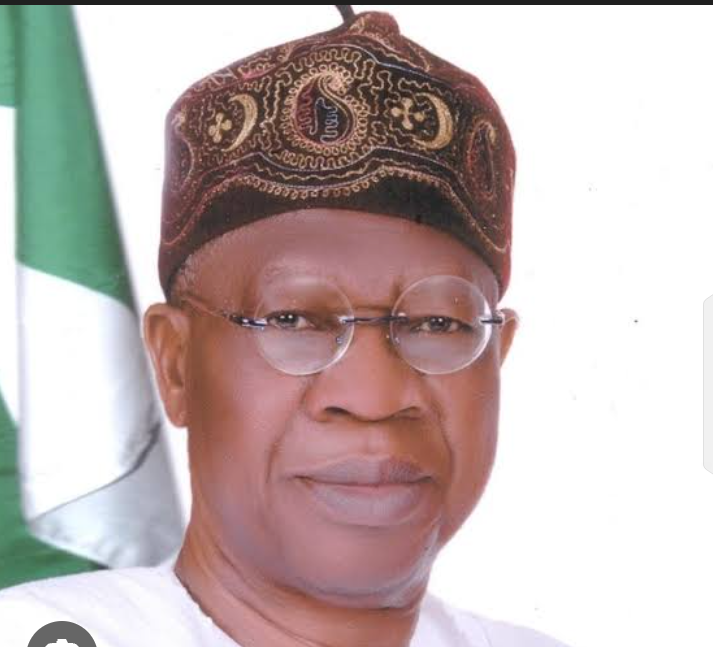

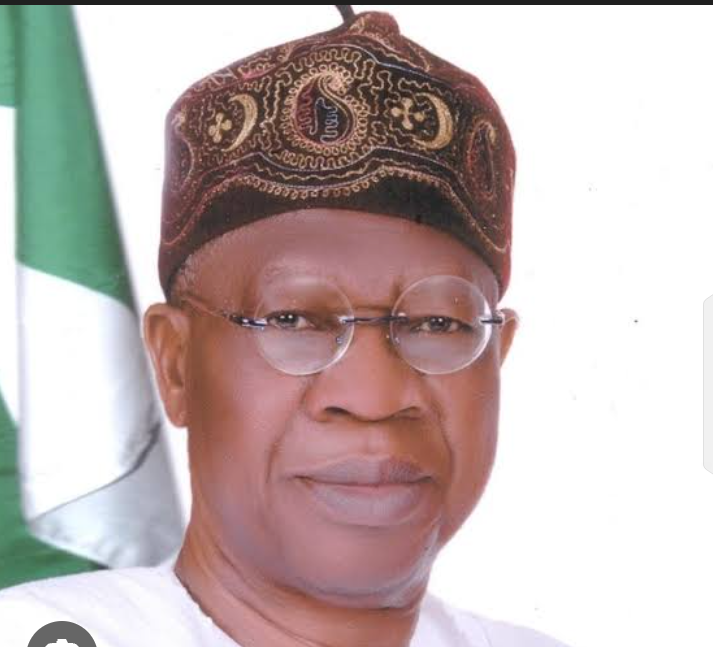

From Prison Plates to Party Staples: Lai Mohammed Sparks Fresh Debate on the True Origins of Jollof Rice

Former Minister of Information, Lai Mohammed, has once again found himself at the centre of a national conversation after making comments that touch on one of West Africa’s most emotionally charged subjects: jollof rice. In remarks that have since gone viral, Mohammed traced the origin of the beloved dish to Senegal, linking its roots to the Wolof people and adding a surprising historical twist by stating that jollof rice was once prepared as food for prisoners.

Speaking candidly on the matter, Mohammed argued that many West Africans passionately defend jollof rice without fully understanding its historical background. According to him, the name “jollof” itself is derived from “Wollof,” a reference to the Wolof ethnic group of Senegal. “When you look at the origin of jollof, it’s actually from the word Wollof and it’s Senegalese and the people don’t understand the origin of jollof,” he said, suggesting that the popular rivalry over which country makes the best jollof often ignores its deeper roots.

Mohammed’s comments went further than just geography. He provided a historical account that startled many listeners, explaining that jollof rice was originally a simple, communal meal associated with imprisonment. “Jollof rice was actually that food that was prepared for prisoners, ‘cos it was that food that was put in one plate, oil, salt, you know, and everything,” he said. According to his explanation, the dish was designed to be filling, affordable, and easy to prepare in large quantities, characteristics that made it suitable for feeding inmates. “So really everything of jollof is Wollof,” he added, reinforcing the cultural and linguistic connection.

The remarks have reignited long-standing debates across social media, where Nigerians, Ghanaians, Senegalese, and other West Africans routinely clash over jollof rice supremacy. For many Nigerians, jollof rice is more than food; it is an identity, a symbol of celebration, and a staple at weddings, birthdays, parties, and festive gatherings. Mohammed’s description of the dish as once being “food for prisoners” struck a nerve, not because it diminished its value, but because it challenged the romanticised history many have grown accustomed to.

Supporters of Mohammed’s view have pointed out that many globally celebrated foods have humble or even grim origins. Across the world, meals that started as survival food for peasants, soldiers, or prisoners later evolved into cultural icons. From French peasant stews to Italian pasta dishes born out of poverty, history shows that the origins of food do not determine their present-day significance. In this light, Mohammed’s comments are seen by some as an attempt to educate rather than insult.

Mohammed also referenced the role of international tourism and historical documentation in shaping the narrative around jollof rice. “I think later the UN Tourism somebody came out on Wikipedia that the origin of jollof is Wollof,” he noted, suggesting that academic and cultural institutions have long acknowledged Senegal as the birthplace of the dish. This claim aligns with widely circulated historical accounts that trace jollof rice to “thieboudienne,” a traditional Senegalese rice dish considered by many food historians to be the ancestor of modern jollof.

Despite these references, reactions in Nigeria have been mixed. While some Nigerians have accepted the historical explanation, others insist that origin does not equal ownership. They argue that Nigerian jollof rice has evolved into something distinct, shaped by local ingredients, cooking methods, and cultural influences. For these defenders, Nigerian jollof is not merely an offshoot of Senegalese cuisine but a reimagined dish that has taken on a life of its own.

Social media platforms have been flooded with humorous memes, heated arguments, and cultural analyses following Mohammed’s remarks. Some users joked that if jollof rice started as prison food, it must be proof of how far creativity can transform necessity into luxury. Others accused the former minister of stirring controversy unnecessarily, especially given Nigeria’s current social and economic challenges. Still, many welcomed the conversation as an opportunity to learn more about West African history and shared cultural heritage.

Food historians and cultural commentators have also weighed in, noting that Mohammed’s comments reflect a broader truth about African cuisine: borders drawn by colonial powers do not neatly divide culinary traditions. Rice dishes similar to jollof exist across the region, from Senegal’s thieboudienne to Ghana’s jollof, Nigeria’s party jollof, Sierra Leone’s jollof rice, and Liberia’s versions. Each country has adapted the dish to local tastes, spices, and cooking styles, making it both shared and contested.

For Senegalese commentators, Mohammed’s remarks have been largely welcomed as overdue recognition. Many Senegalese food enthusiasts have long argued that their country’s contribution to West African cuisine is often overlooked in popular narratives dominated by Nigerian-Ghanaian rivalries. Mohammed’s statements, in their view, simply reaffirm what history has already recorded.

At the same time, critics caution against reducing jollof rice to a single origin story. They argue that food history is rarely linear and that dishes evolve through trade, migration, and cultural exchange. The Wolof people may have laid the foundation, but generations of West Africans across different regions have contributed to the dish’s transformation into what it is today.

What remains clear is that jollof rice continues to hold immense cultural power. Whether served at a roadside buka, a lavish wedding, or a diplomatic event, it remains a symbol of community and celebration. Mohammed’s comments, rather than diminishing jollof’s status, have reminded many of its journey from simplicity to stardom.

In attempting to “educate Nigerians,” as his supporters frame it, Lai Mohammed has once again demonstrated how food can spark national conversations about history, identity, and pride. The debate over jollof rice’s origin is unlikely to end anytime soon, but perhaps that is part of its magic. In a region with shared histories and intertwined cultures, jollof rice remains both a point of contention and a unifying dish, proving that even a meal once meant for prisoners can become a crown jewel of West African cuisine.