Terror Returns to Kaduna: Fear and Outrage as ‘Repentant’ Bandits Steal 97 Cows in One Week

Residents of several farming communities in Kaduna State are once again living in fear after a wave of renewed terror allegedly carried out by individuals previously labeled as “repentant” bandits. In a troubling development that has sparked outrage and despair across the state, a group of impoverished farmers has raised

Residents of several farming communities in Kaduna State are once again living in fear after a wave of renewed terror allegedly carried out by individuals previously labeled as “repentant” bandits. In a troubling development that has sparked outrage and despair across the state, a group of impoverished farmers has raised the alarm that these men, once believed to have abandoned their criminal past, have resumed violent activities and stolen a staggering 97 cattle within just one week. For communities already grappling with economic hardship, insecurity, and uncertainty, the resurgence of these attacks has reopened old wounds and deepened the sense of vulnerability that has plagued rural Kaduna for years.

The affected farmers, many of whom depend entirely on their livestock for survival, say they have been left devastated. According to a representative who spoke on their behalf, the losses recorded in the span of seven days are not only shocking but also indicative of a larger failure in the state’s deradicalization and reintegration efforts. He provided a breakdown of the stolen cattle, detailing how the animals were taken from different settlements in brazen nighttime raids carried out with precision and confidence. The farmers insist that the culprits are not new criminals but individuals known to them—men who had previously surrendered, claimed to abandon violence, and were reportedly integrated back into society under government-backed rehabilitation programs.

Residents say the attacks began slowly, with isolated incidents that many initially dismissed as the work of petty thieves. But the trend quickly escalated into a coordinated pattern of raids marked by intimidation, threats, and outright violence. The bandits reportedly invaded grazing fields and livestock pens, carting away herds that families had spent years building. In communities where cattle are not just property but symbols of economic stability, social value, and generational legacy, the theft represents a crippling blow. Several farmers are now left with nothing, their livelihoods wiped out in a matter of days by criminals they once believed had turned a new leaf.

The allegations have sparked heated debate across Kaduna State, particularly surrounding the controversial program that seeks to rehabilitate bandits who voluntarily surrender. Critics argue that the system lacks transparency, proper monitoring, and accountability, leaving room for abuse by individuals who pretend to have reformed while secretly maintaining ties to their criminal networks. For many residents, the latest wave of cattle theft is proof that the community’s willingness to forgive has been taken for granted, and that the government’s strategy may require urgent reevaluation.

Local leaders and concerned citizens say the most painful aspect of the situation is the betrayal of trust. Several of the farmers reported that some of the so-called repentant bandits who now terrorize them once lived among them peacefully after their supposed transformation. They were welcomed, supported, and given the benefit of the doubt, all in hopes of fostering peace. Instead, the farmers say they now feel deceived and left at the mercy of men who exploited their goodwill. Many believe that without stricter security measures and thorough evaluation of those claiming repentance, the cycle of violence will never end.

Fear has now taken hold of the affected communities as residents brace for what may come next. Many farmers say they no longer sleep at night, choosing instead to keep vigil around their remaining livestock. Others have fled to nearby towns, abandoning their homes and farms, unsure of when it will be safe to return. The psychological toll is immense. Children are reportedly too afraid to attend school, women avoid going to markets or farms, and men who once worked in groups for safety now find themselves outnumbered and outmaneuvered by heavily armed criminals.

Community elders are calling for immediate government intervention, urging security agencies to comb the affected areas and recover the stolen cattle. They argue that if urgent steps are not taken, the criminals may become emboldened, leading to more casualties and deeper insecurity. They also emphasized that the losses extend beyond the stolen animals; they represent shattered dreams, broken families, and a worsening cycle of poverty. Many of the victims had taken loans to expand their livestock, and now face the reality of repaying debts for cattle they no longer have.

As the news spreads, civil society organizations have also expressed concern, warning that Kaduna’s rural communities are at a breaking point. Echoing the farmers’ grievances, activists highlight that Nigeria’s broader insecurity crisis is being fueled by the inability of authorities to enforce sustainable solutions. They argue that relying solely on amnesty or reintegration without simultaneous investments in intelligence gathering, border security, surveillance, and community policing is a short-sighted approach. If repentant bandits can easily revert to violence, they say, then the system is fundamentally flawed.

Meanwhile, the Kaduna State government has yet to issue a full statement addressing the latest attacks, but officials familiar with security matters confirm that investigations are underway. The farmers hope these investigations will not be another bureaucratic formality that leads nowhere. They fear that without decisive action, the damage could expand beyond cattle theft to full-blown attacks on homes, markets, and farmlands—a situation they experienced in the past and desperately hope not to relive.

Security experts warn that the situation reflects a troubling pattern seen in several states where armed groups exploit reintegration programs without committing to actual behavioral change. They say the government must reassess how it identifies truly repentant individuals and ensure that those reabsorbed into society are closely monitored to prevent a relapse into crime. The experts also urge communities to report suspicious activities early and cooperate with security forces, even though trust between residents and authorities has eroded over time.

For now, the mood in Kaduna’s rural belt is a mix of anger, sorrow, and uncertainty. Families who once prayed for peace say their hopes are fading as the same criminals they forgave return to terrorize them. The theft of 97 cattle in a single week is more than just a statistic—it is a reminder of how fragile life has become for Nigeria’s rural poor. As the state grapples with escalating insecurity, one thing is clear: the promise of reconciliation remains unfulfilled, and until it is backed by effective security measures, peace will remain out of reach for the farmers who now watch their land with fear instead of hope.

Share this post

Related Posts

Angela Okorie Caught in Family Drama as Ex-Boyfriend Oil Money Makes Shocking Allegations About Her Brother

Nollywood actress Angela Okorie has found herself in the eye of a storm once again,...

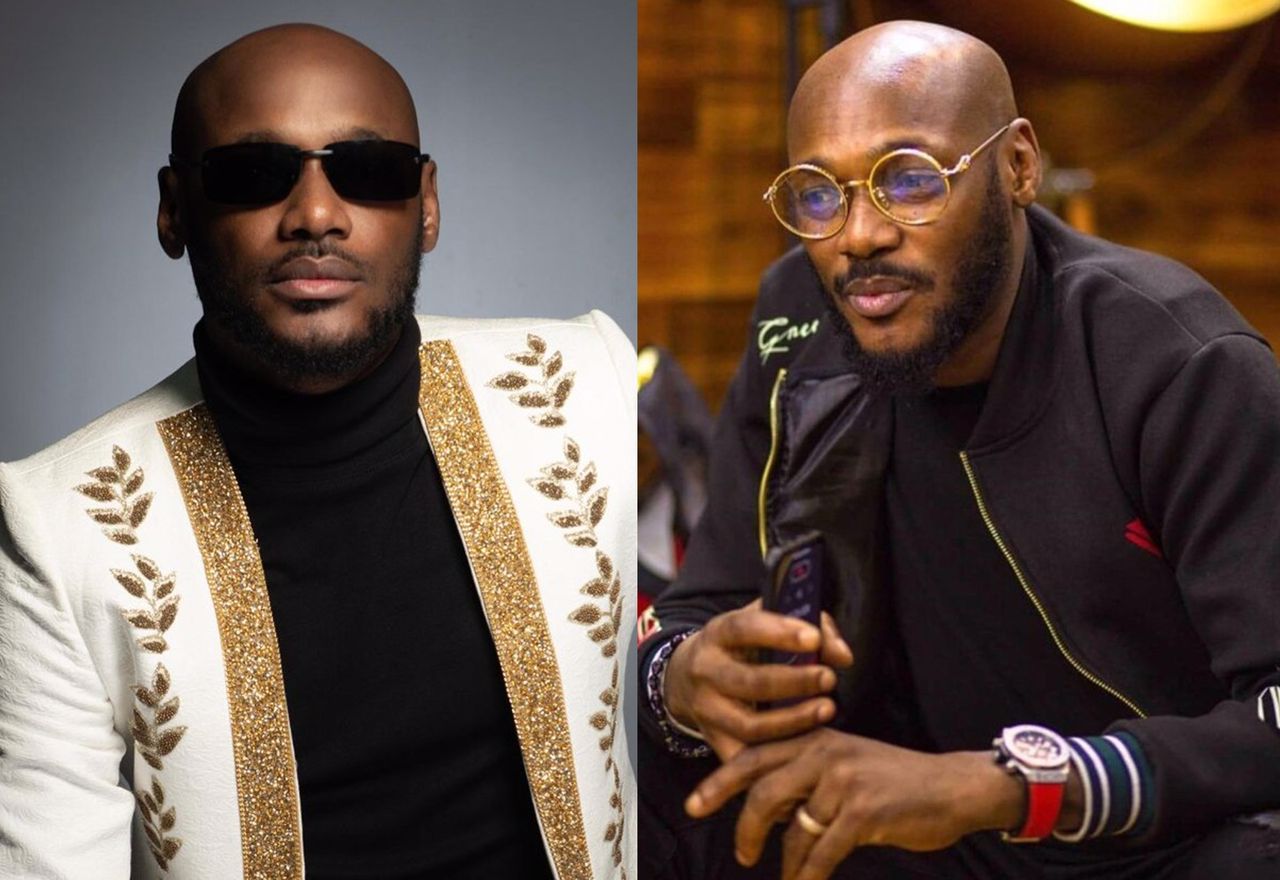

“I Know People Wey Ready Make I D!e” – 2Baba’s Haunting Confession Sends Shockwaves Through Fans

Legendary Nigerian music icon, Innocent Ujah Idibia, better known as 2Baba, has once again stunned...

“Marriage Is a Partnership”: Daniel Etim Effiong Opens Up About Attraction, Love, and Honesty in Modern Relationships

Nigerian actor and filmmaker Daniel Etim Effiong has stirred widespread conversation across social media after...