In a dramatic turn of events heavy with geopolitical implications, Madagascar’s new leader, Michael Randrianirina, held a formal meeting with the Russian ambassador, marking a swift shift in foreign alignment following last week’s military takeover. The meeting underscores not only an abrupt change in domestic rule but also signals Madagascar’s possible new direction on the international stage.

The island nation of Madagascar has been gripped by turmoil since protests erupted in late September, driven by widespread power and water outages, pervasive youth unemployment, and public frustration with corruption. These protests—the lifeblood of a young “Gen Z” movement—culminated in a rapid military takeover when the elite CAPSAT unit refused orders to suppress the demonstrators. On 12 October 2025, CAPSAT led the seizure of key government institutions, the parliament voted to impeach the outgoing president, Andry Rajoelina, who fled the country, and Colonel Randrianirina announced the military was now in charge.

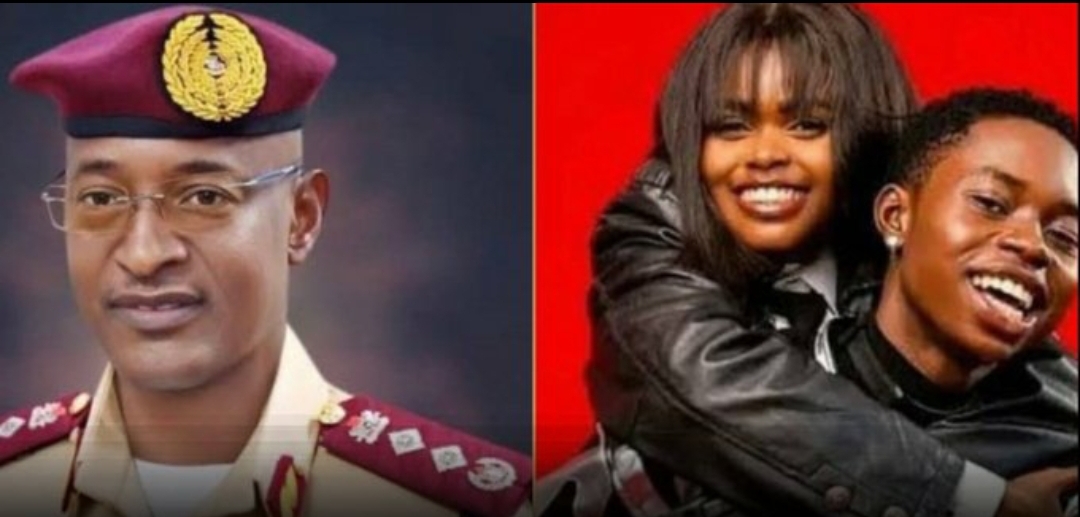

Just days later, on 17 October, Randrianirina was sworn in by the High Constitutional Court as the interim head of a “refoundation” government. He pledged up to two years of transitional rule before elections would be held. It is against this backdrop that the meeting with the Russian envoy took place.

In that meeting, which has been reported by Russian state-affiliated media, Randrianirina and Andrey Andreyev (the Russian ambassador to Madagascar) discussed “friendly cooperation between Russia and Madagascar during the transition period.” According to the new president’s interview published by Sputnik Africa, he spoke of a “total break” with the past and said: “What we’re going to do is find partners who will work with us in a win-win manner.”

The sudden outreach to Russia sends a strong signal. For decades, Madagascar’s politics and economy have been closely entwined with France, its former colonial power, and European partners. Yet the new leadership appears to be recalibrating its alliances. Analysts note that Russian diplomatic representatives have already met with Randrianirina twice, emphasising willingness to deepen the partnership with Madagascar. For Madagascar’s youth-led protesters, however, the concern is whether the new government will deliver services and reform—rather than merely replace one elite with another. “We really fighting for system change, not to swap one president for another,” said one leader from the Gen Z movement.

The meeting also puts the spotlight on strained Franco-Malagasy relations. While Paris has historically held strong influence in Antananarivo’s corridors of power, many in Madagascar now see France as supportive of entrenched elites despite persistent poverty and service failures. One French-Malagasy former gendarme recently criticised France’s position on Madagascar’s political crisis, heightening anti-French sentiment. Meanwhile, continental bodies responded sharply to the takeover: the African Union suspended Madagascar following the coup, citing the unconstitutional change of power.

The new president’s meeting with the Russian ambassador is therefore more than a diplomatic photo-op—it hints at a strategic orientation in which Madagascar may pivot towards non-Western partners. Given Russia’s global posture in Africa—seeking access, influence, resources, and alliances—this moment could mark the starting point of a broader realignment in Madagascar’s international engagements.

Domestically, the stakes are enormous. The promises made by Randrianirina’s team are bold: root out corruption, fix chronic infrastructure failures, address youth unemployment, and set the stage for a civilian government within 18-24 months. But historians of the region warn that military-led transitions often fail to translate street-level change into lasting structural reform. Madagascar’s young population, with a median age under 20, hopelessly watched the previous regime and critical services falter.

Internationally, the optics will matter. Western governments and multilateral institutions warned that the overthrow of a democratically elected government—even one widely perceived as underperforming—damages constitutional norms and regional stability. With Moscow now engaging Madagascar openly, Western actors such as the European Union may find their influence challenged unless they respond quickly. According to one commentary, “Europe needs to show that it can be as — if not more — proactive than other global actors.”

As for Russia, the move into Madagascar could be seen as part of a broader pattern of diplomatic and security footprints across Africa, where Moscow is courting states often frustrated with Western conditionality and influence. Madagascar’s strategic location, resources, and logistical possibilities may make it an attractive partner.

For now, all eyes are on Antananarivo. Will the new government follow through on its reform rhetoric? Will partnerships with Russia reshape Madagascar’s development path or geopolitics? And crucially, will the youth who sparked the uprising see their demands for electricity, clean water, jobs, and accountability met this time? The meeting with the Russian ambassador marks a new chapter—but whether that chapter will be one of renewal or continuity remains deeply uncertain.