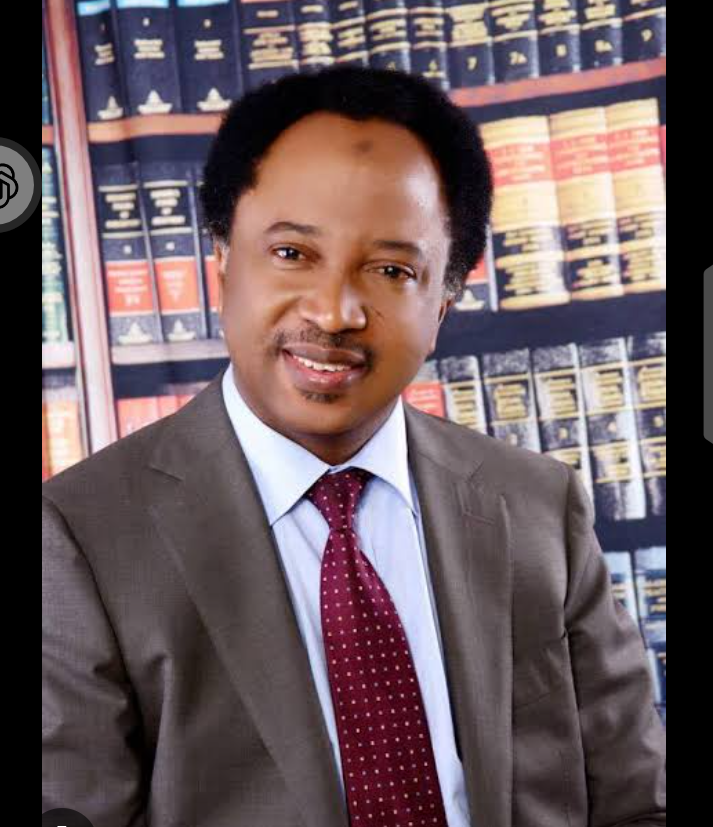

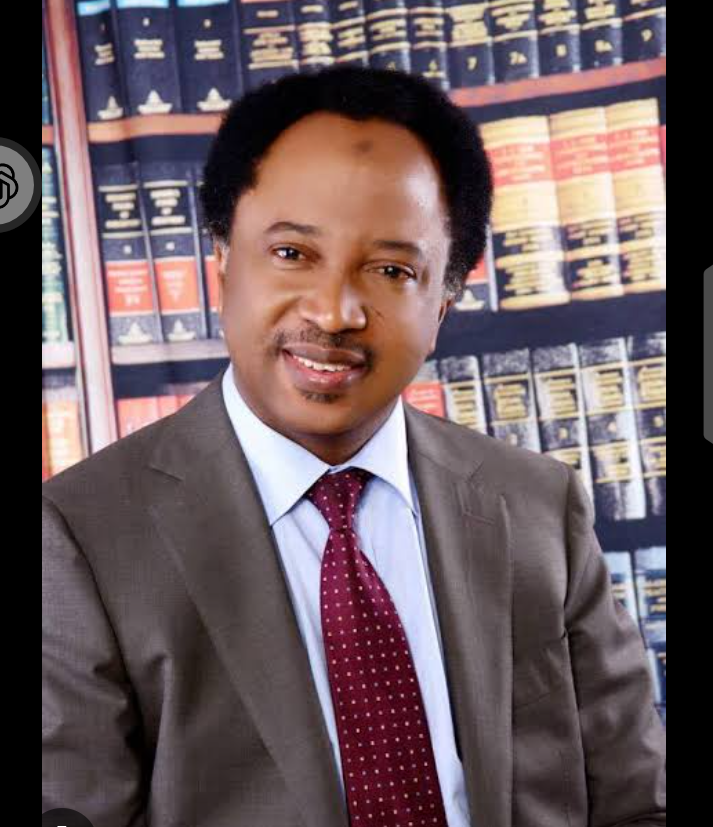

“They Can Strike, But They Can’t Save Us”: Shehu Sani’s Warning as Nigeria Debates U.S. Military Involvement

As debates continue to swirl around recent military strikes on terrorist targets in Nigeria’s North-West, former Kaduna Central senator and human rights activist Shehu Sani has injected a sobering note into the national conversation, reminding Nigerians that lasting peace and security cannot be outsourced to foreign powers. His comments, posted on X, come amid heightened public scrutiny of reports that the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM) carried out airstrikes in coordination with Nigerian authorities, targeting terrorist cells operating in parts of the country long plagued by violence and insecurity.

Sani’s statement neither dismisses the potential tactical value of foreign military cooperation nor blindly celebrates it. Instead, it strikes a careful balance, acknowledging that if the reported strikes were indeed a joint operation with Nigerian authorities, as AFRICOM suggested, then such action could be considered “conscionable.” In a region where terrorist groups have entrenched themselves deeply, operating as what Sani described as “cancerous cells,” many Nigerians have grown weary of endless bloodshed, kidnappings, and displacement. For communities living under the constant threat of armed groups, any blow against terrorists can feel like a rare moment of relief.

However, Sani’s broader message goes beyond the immediate military headlines. He challenges the idea that external force, no matter how powerful, can serve as a permanent solution to Nigeria’s security crisis. “They can strike, but they can’t eternally fight our battles,” he wrote, stressing that the ultimate responsibility for peace rests squarely with Nigerians themselves. This assertion touches on a long-standing tension in Nigeria’s security discourse: the fine line between beneficial international cooperation and dangerous dependency.

The reported involvement of the U.S. military has reopened old wounds and debates about sovereignty, capacity, and trust in Nigeria’s own institutions. Over the years, successive governments have partnered with foreign allies for intelligence sharing, training, and logistical support in the fight against terrorism. While such collaborations have sometimes yielded results, they have also fueled public unease, particularly when details are scarce or narratives appear inconsistent. For many Nigerians, the question is not whether foreign assistance is useful, but whether it subtly signals a failure of the state to fully protect its own citizens.

Sani also addressed a narrative that often surfaces whenever violence erupts in the North: the claim that terrorist attacks are targeted at a single faith. He rejected this framing as “absolutely false and misleading,” emphasizing that terrorists have inflicted suffering across religious and ethnic lines. By doing so, he pushed back against attempts to reduce a complex security crisis into a simplistic religious binary. Such narratives, he warned implicitly, risk deepening divisions and distracting from the real enemy — armed groups that thrive on chaos, fear, and fragmentation.

His intervention arrives at a time when Nigerians are increasingly vocal about insecurity, especially in the North-West, where banditry and terrorism have devastated rural communities. Villages have been raided, schools shut down, and livelihoods destroyed, creating a climate of fear that stretches beyond any single state. In this context, news of foreign airstrikes naturally triggers mixed reactions: relief for some, suspicion for others, and deep reflection for voices like Sani’s who see both the urgency and the danger in relying too heavily on external forces.

The former senator’s use of the phrase “they live by the sword” underscores the ruthless nature of terrorist groups operating in the region. Yet his insistence that Nigeria’s peace cannot be permanently guaranteed by outsiders speaks to a deeper issue — the need for structural, political, and institutional reforms at home. Military strikes, whether domestic or foreign-backed, may neutralize specific targets, but they do not automatically resolve the underlying drivers of insecurity, such as poverty, weak governance, corruption, and the erosion of trust between citizens and the state.

Sani’s comments also subtly reflect a broader African concern about foreign military footprints on the continent. Across Africa, there has been growing skepticism toward external interventions, fueled by historical experiences and recent geopolitical shifts. While Nigeria’s situation is unique, it exists within this wider context, where citizens increasingly question whether foreign involvement genuinely serves local interests or merely offers short-term fixes without long-term accountability.

At the same time, Sani did not call for isolationism. His acknowledgment that foreign powers can “complimentarily or unilaterally strike” suggests an understanding that international cooperation has a place in modern security strategies. What he cautions against is the illusion that such cooperation can replace national resolve, capacity-building, and collective responsibility. In his view, strikes may disrupt terrorists temporarily, but without sustained domestic effort, the cycle of violence will simply regenerate in new forms.

Public reaction to Sani’s statement has been intense, reflecting the emotional weight of the issue. Some Nigerians agree wholeheartedly, seeing his words as a necessary reminder of self-reliance and sovereignty. Others argue that given the scale of the threat, Nigeria cannot afford to turn away any help, especially from a global military power like the United States. This divide mirrors a broader national anxiety: the fear that insecurity is outpacing the state’s ability to respond effectively.

Ultimately, Shehu Sani’s intervention reframes the conversation from one of celebration or condemnation of foreign strikes to a more uncomfortable, introspective question: what kind of country does Nigeria want to be in the long run? A nation that occasionally benefits from foreign firepower, or one that builds the internal strength to secure its people without depending on external saviors? His message suggests that while allies may assist, the burden of peace cannot be shifted elsewhere.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with terrorism and banditry, Sani’s words serve as both a caution and a challenge. They remind policymakers and citizens alike that security is not merely about who pulls the trigger, but about who takes responsibility. In a moment dominated by breaking news and dramatic headlines, his statement stands out for its insistence on agency, accountability, and the hard truth that no foreign power, however strong, can fight Nigeria’s battles forever.